The White Dragon School Blog

Snake Strikes of Choy Li Fut Kung Fu

It was during the Tang Dynasty (617-960) that the martial arts really began to flourish in China. Because of the Middle Kingdom’s increased interaction with the regions beyond its borders, its fighting arts were spread far and wide, and they are believed to have influenced numerous combat systems practiced in Korea, Okinawa, Vietnam and other nations.

This expanded interest in the martial arts and brought with it the accelerated development of open-hand fighting styles that involved internal training methods and pressure-point strikes. In particular, the monks of Shaolin Temple—some of whom were proficient fighters prior to their joining the monastery—became renowned for their prowess at open-hand combat. An important part of their curriculum was snake strikes.

Cult of the Snake

Historically, Asian cultures have viewed the snake quite differently than have Occidental cultures. Partly because Asians were not exposed to Christianity’s account of the Garden of Eden, they did not develop the same loathing for members of the ophidian order that Westerners still seem to have. Hence, citizens of China, Korea, and Japan were never hesitant about treating themselves to the culinary delights and rejuvenating properties of snakes and snake byproducts.

Chinese martial artists also paid attention to their scaly reptilian friends. Oftentimes, snake handlers and trappers were expert martial artists, and they frequently studied their quarry to see how each species killed its prey and avoided the attacks of predators.

That impromptu field research led to one of the more interesting martial arts developments of the Tang Dynasty: the Shaolin snake style, or se ying. It evolved as a set of open-hand techniques that target the enemy’s vital points: temples, eyes, throat, solar plexus, armpits, and groin. So popular were snake strikes that at least one Chinese art, Choy Li Fut kung fu, would eventually adopt the serpent tactics and attitudes for one of its advanced internal forms—named, appropriately enough, the snake form.

Power of the Snake

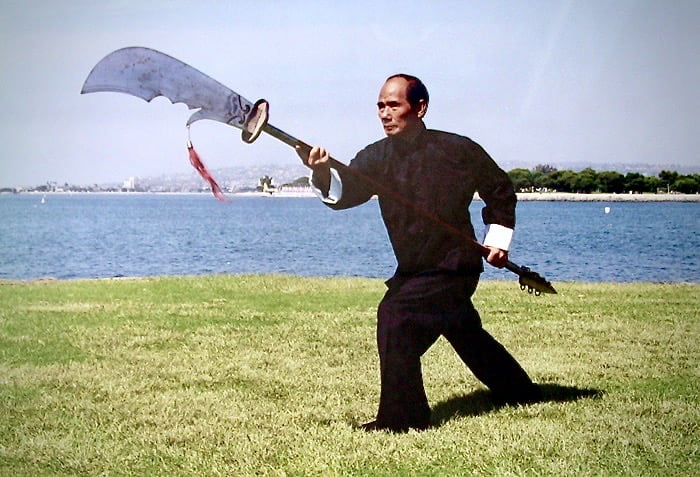

Nathan Fisher, a San Diego-based Choy Li Fut instructor and the head of five White Dragon Martial Arts Schools, considers the snake form to be one of the more important concepts in Choy Li Fut. “All the movements in se ying are open-hand techniques,” he says. “The power is soft and flowing, designed to penetrate continuously into pressure points. It’s a fighting concept that anyone can use successfully, whether they are man or woman, young or old.”

Choy Li Fut’s snake form closely mimics the serpent’s essence and movements. For instance, an angry cobra coils itself before it attacks. From that position, it straightens its body with devastating speed and accuracy, lashing out to strike its prey. Although it is able to generate a great deal of force from this action, at no time does the cobra pit its strength against that of a larger adversary.

Another advantage the snake enjoys—one that is perhaps even more important than its unique striking technique—is its ability to develop and release chi (internal energy) every time it strikes. It cultivates the same chi that martial artists strive to control so they can execute their techniques with superior focus and penetration.

Since the snake is normally calm and relaxed, it possesses more chi than most other animals. When that internal energy is augmented with proper striking technique, it produces a formidable and powerful blow. A similar combination was responsible for the Shaolin monks’ almost superhuman ability to fight, and those same tactics eventually became part of Choy Li Fut.

Anatomy of the Snake

The serpentine side of Choy Li Fut differs from other animal styles of kung fu because of the relaxed, almost floating way in which the practitioner moves and the hard and soft ways in which he delivers power. Most animal styles teach students to use a tense, aggressive force to strike down an adversary. For instance, the tiger style relies on strictly external strength, and practitioners are noisy and active—with some even producing loud sounds to add force to their blows.

In contrast, the snake’s energy is quiet and internal. The practitioner makes no sound as he maneuvers with fluid footwork and administers a soft, penetrating blow. Fist strikes are not used in the style; instead, penetrating palm and fingertip attacks are emphasized. Because blocks and strikes are made simultaneously, there is no difference between defense and offense. One can become the other in a heartbeat. For example, a coiled or circular snake technique can be a defensive beginning that changes into a straight offensive strike. During this transformation, smoothness is more important than speed.

Choy Li Fut includes several types of fingertip strikes within its repertoire of snake techniques. One of them requires the practitioner to recreate the animal’s tongue by extending his index and middle fingers while folding back the others. Called “snake throws out its tongue,” the technique usually targets the opponent’s vital points.

Another Choy Li Fut fingertip strike involves placing all four fingers together to form an attacking surface that resembles a cobra’s head. The practitioner extends his arm to strike in much the same way a cobra strikes at its prey by extending its coiled body. Called gin ji, or spear-palm technique, it is an upper block that easily converts into a deadly blow.

The Choy Li Fut snake form includes a unique feature called “anchor hand.” A combination of a blocking technique and a hooking or grabbing hand movement, it relies on “sticking energy” to trap and control the opponent’s striking arm.

In addition to imitating the snake’s fighting techniques, kung fu practitioners strive to duplicate the snake’s attitude. “An animal’s fighting habits are based upon its instinctive nature,” says Fisher, “and it’s important to preserve that nature in the martial form”.

Therefore, it’s essential for martial artists who practice the snake form to keep their body supple and in motion at all times. Since the form uses both hard and soft power, they must be able to deliver soft, circular force with their arms and hard, external power with their hands. The key to cultivating this ability lies in developing flexible and relaxed waist action, Fisher says.

Benefits of the Snake

The most important contribution the Choy Li Fut snake form makes to a martial artist’s development has to do with chi. Chi flows naturally from a relaxed and concentrated body. Relaxation contributes to softness and flexibility, and concentration leads to calmness and clear thinking. Those attributes will prove useful to any martial artist.

When snake stylists work to develop their chi, they imitate the relaxed posture of the snake and learn to generate internal energy with every movement. To help them relax, they practice the form slowly. Soon, each portion of their body is connected by internal energy. Chi moves through their arms and out to their fingertips, where it becomes a penetrating force. When they are not touching their opponent, they appear to possess no strength at all, but their soft touch becomes a magical sting as soon as it connects with a foe.

Although the snake form may look soft, in an actual fighting situation the actions are speedy and the strikes are forceful. Upon contact, the practitioner’s normal energy reserves can be amplified up to seven times.

But the benefits of practicing the snake strikes of Choy Li Fut are more than physical. A snake possesses a special spirit, Fisher says. “If snake stylists cultivate their chi properly, they will be calm enough to mentally look inside their body, feeling peaceful and quiet. Very little of an external nature bothers them. When they develop the proper snake spirit, they can feel the energy flow from their spine through their arms and out their fingertips.”

That quality allows Choy Li Fut practitioners to move calmly and deliberately before they strike or block. As soon as they decide to take action, their movements can penetrate their opponent’s defenses like a bolt of lightning. When the conflict is over, they can return to their naturally calm state and go about their business.

“The Snake Strikes of Choy Li Fut Kung Fu” by Jane Hallander was originally published in the September 1999 issue of Black Belt Magazine.