The White Dragon School Blog

Researchers Study Tai Chi’s Health Benefits

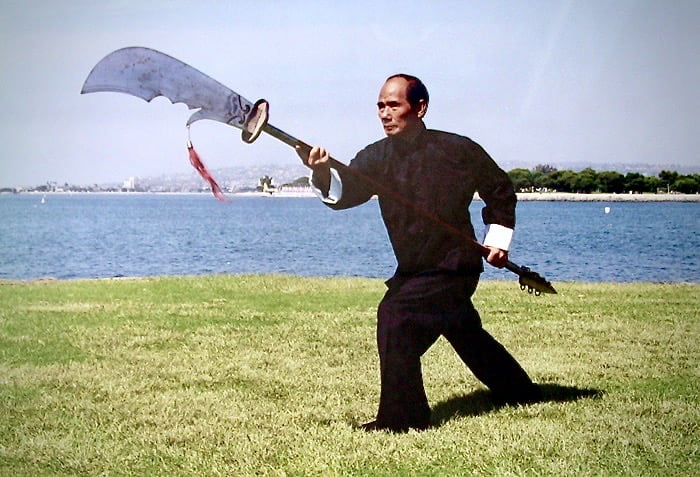

Tai Chi, the centuries-old Chinese mind-body exercise, now gaining popularity in the United States, consists of slow-flowing, choreographed meditative movements with poetic names like “wave hands like clouds,” “dragons stirring up the wind,” and “swallow skimming the pond”. Although Tai Chi may evoke images of the natural world, it also focuses on basic components of overall fitness: muscle strength, flexibility, and balance.

“Doing Tai Chi makes me feel lighter on my feet,” says Catherine Kerr, a Harvard Medical School (HMS) instructor who has practiced for 15 years. I’m stronger in my legs, more alert, more focused, and more relaxed—it just puts me in a better mood all around.”

Meditation, motor learning, and attentional focus have all been shown in numerous studies to be associated with training-related changes—including, in some cases, changes in actual brain structure—in specific cortical regions.

Western scientific understanding of Tai Chi’s possible physiological benefits is still very rudimentary. Tai chi is a very interesting form of training because it combines a low-intensity aerobic exercise with a complex, learned, motor sequence. Meditation, motor learning, and attentional focus have all been shown in numerous studies to be associated with training-related changes—including, in some cases, changes in actual brain structure—in specific cortical regions.

Scholars say Tai Chi grew out of Chinese martial arts, although its exact history is not fully understood, according to one of Kerr’s colleagues, assistant professor of medicine Peter M. Wayne, who directs the Tai Chi and mind-body research program at the Osher Center. “Tai chi’s roots are also intertwined with traditional Chinese medicine and philosophy. Though these roots are thousands of years old, the formal name Tai Chi chuan was coined as recently as the seventeenth century as a new form of kung fu, which integrates mind-body principles into a martial art and exercise for health.”

Tai chi, considered a soft or internal form of martial art, has multiple long and short forms associated with the most popular styles taught: Wu, Yang, and Chen (named for their originators). Plenty of people practice the faster, more combative forms that appear to resemble kung fu, but the slower, meditative movements are what many in the United States—where the practice has gained ground during the last 25 years—commonly think of as tai chi.

Surveys, including one by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, have shown that between 2.3 million and 3 million people use tai chi in the United States, where a fledgling body of scientific research now exists. The center has supported studies on the effect of tai chi on cardiovascular disease, fall prevention, bone health, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis of the knee, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic heart failure, cancer survivors, depression in older people, and symptoms of fibromyalgia. One study on the immune response to varicella-zoster virus (which causes shingles) suggested in 2007 that tai chi may enhance the immune system and improve overall well-being in older adults.

However, “in general, studies of tai chi have been small, or they have had design limitations that may limit their conclusions,” notes the center’s website. “The cumulative evidence suggests that additional research is warranted and needed.”

Original article by Nell Porter Brown, Harvard Magazine.

1 Comments

[…] to build strength, flexibility, and endurance. Proper Tai Chi practice is a time tested method of improving one’s health while at the same time learning […]